Although the first invention occurred much earlier in China and Korea, the genesis of modern printing by means of a printing press using metal movable type is rightly traced to Gutenberg ’s publication of the Bible, which changed the nature of document production- and transformed the world.

Woodblock printing was invented in China early in the sixth century when a carved board was inked and used to print multiple copies of a page. The Chinese also modified the method to create individual characters in the 1040s, although their use of such technology was limited by the requirement of having to create the thousands of individual characters neede for Chinese writing. Korea was the first country to adopt China’s woodblock printing and the first to devise metal movable type for individual characters, which was done to print the Buddhist document Jikji in 1377. But the complexities of Asian languages made the use of metal movable type better suited for publishing Western alphabetical languages.

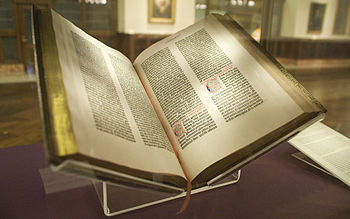

The great breakthrough occurred in the 1450s when a blacksmith and printer in Mainz, Germany named Johannes Gutenberg (1398-1468) spent four years perfecting new printing methods in order to produce an exquisite edition of the Vulgate, the fourth-century Latin-language version of the Bible.

Working with a crew of at least twenty ink-stained assistants, Gutenberg developed his fine printing technology largely from scratch, experimenting with different inks, papers, and processes until he had found the right one. Instead of traditional water-based inks, he chose oil-based ink of the highest quality and mastered its manufacture to the most exacting standards. The best paper was brought in from Italy. Through trial and error, he developed a special metal alloy that would melt at low temperature but remain strong enough to withstand being squeezed in a press. He found just the right method to make individual letters by casting them in a specially created sand-cast mold, also devising ways to sort, store, and maintain the type so it could be used repeatedly with good effect. His fonts were expertly designed and crafted with absolute precision, with 292 different blocks of type, including as many as six versions of the same letter, made into different widths to enable each to be squeezed to fit in a tight space if needed, down to the millimeter. His custom-made wooden printing press, modeled on a winepress, enabled the operator 2 print pages at a much faster rate than any woodblock press and the quality of the finished product was excellent.

Notable for its regularity of ink impression, harmony of layout, and other qualities, the 1,286-page Gutenberg Bible ( also known as the “forty-two-line Bible,” “ Mazarin Bible,” or “B42”) was hailed as a masterpiece.

Scholars today sing that somewhere between 160 and 185 copies were printed, of which 48 have survived. The Gutenberg Bible had a profound effect on printing and fueled an information revolution.